When we picture the gods of ancient Egypt, we often conjure images of stoic, animal-headed figures carved into temple walls or painted on papyrus. The fact that Egyptians’ comfort with divine contradiction and fluidity reveals a worldview fundamentally different from many modern, dogmatic faiths. Here we explores some aspects about this region where villains were also heroes, fearsome monsters were gentle guardians, and the divine could be as changeable as life itself.

The Villain or the Guardian?

We often learnt that the god Seth murders his own brother, the benevolent king Osiris and seizes the throne of Egypt for himself.

He plays a archetypal villain and establishes as a force of chaos and conflict. Yet this was only one facet of his complex character. At times, the king revered him as an ancestor god, a source of legitimate royal lineage, a powerful protector of Re and an indispensable guardian of cosmic order. Seth’s duality challenges any simple “good vs. evil” narrative, revealing a sophisticated understanding that divine figures could embody contradictory—but equally vital—roles within the cosmos.

Fearsome Monster or Nurturing Guardian?

The Hippo Goddesses’ appearance composites of terrifying attributes: pregnant woman’s body, lion’s full paws, hippopotamus’ sharp muzzle and small ears and crocodile’s sharp teeth and scaly tail. Their hybrid and terrifying appearance wasn’t a sign of malice; it was a symbol of the powerful guardianship they offered to those who needed it most — to protect “vulnerable individuals especially women and young children.

God in Dynamic Facets

Hathor, the sky god, could appear as a woman wearing a distinctive head ornament of cow horns cradling a sun disk, but could also manifest fully as a cow, symbolizing fertility; in other contexts, she might take the form of a human-headed snake or an emblematic fish. She exemplifies how a deity can change forms when serving different roles and powers. This ability to shift form was a core feature of the Egyptian understanding of divinity, allowing a single god to interact with the world in a multitude of ways.

Thoth the deity of writing, wisdom, the moon, and healing, also has different domains. Thoth can be represented in the form of two different animals-most commonly an ibis but also a baboon. By the Old Kingdom, he frequently manifests as an ibis-headed man when carrying out a more active role, such as writing or giving life. In the New Kingdom, he often takes baboon’s shape as the healer of the wounded eye of Horus and as the god who travels to Nubia to bring back Re’s missing daughter, the Faraway Goddess.

Creation of the World: the Additive mythology

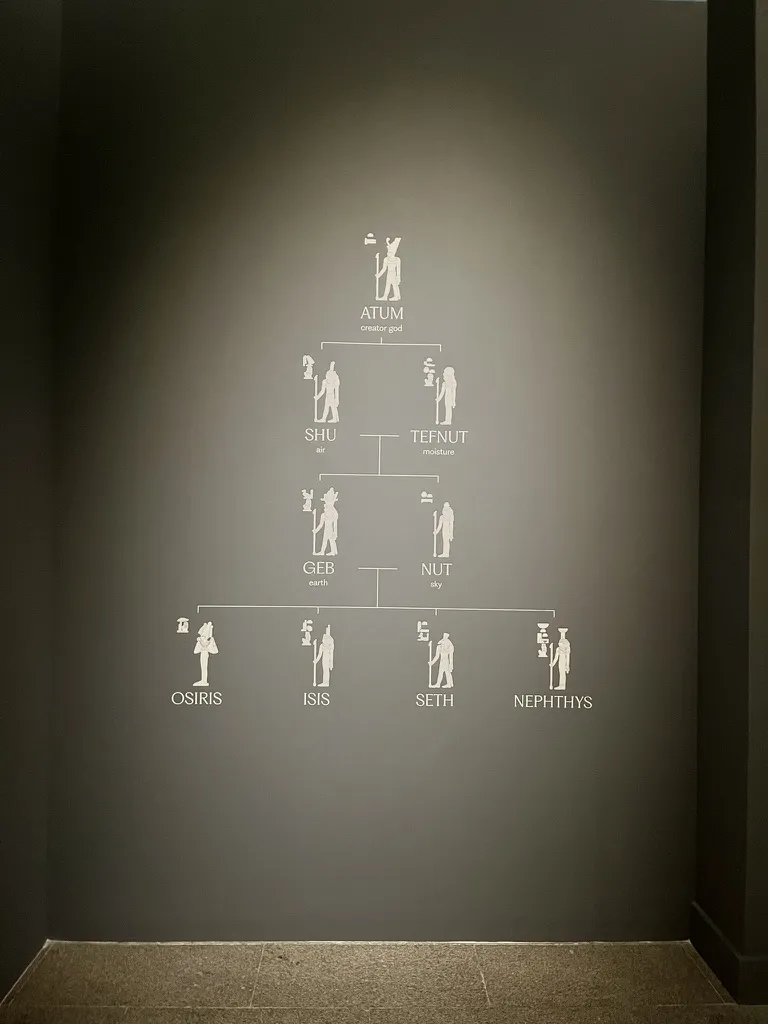

In ancient Egypt, the creation of the world was “the subject of multiple ancient Egyptian myths,” with different cities and traditions offering their own valid accounts. For instance, in the religious center of Heliopolis, the cosmos was believed to have been formed by the deities of the Ennead, a group of nine gods descending from the creator, Atum. Meanwhile, in the city of Memphis, the world was understood to have been created by the god Ptah “through the act of speech.” This multiplicity of explanations demonstrates the complex nature of the belief system of ancient Egyptian mythology combining manifold views on a single topic.

The ancient Egyptians cope with personnel worries surrounding health, childbirth, competition, and love from the deities. Through depictions in tombs, temples, and shrines, deities could “enter sacred spaces and become active participants in rituals.” The carved stone or painted wood became a physical vessel for the god’s spirit, allowing for direct interaction between humanity and the divine. These images were a vital connection between the human and divine worlds, turning sacred spaces into living arenas where gods and mortals could meet.

References:

[1] The Met Museum: Divine Egypt